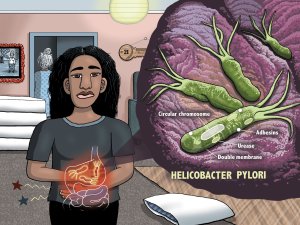

Academic pharmacist Nataly Martini provides key information on Helicobacter pylori pathophysiology, diagnosis and evidence-based treatment strategies to enhance patient outcomes

Ebb and flow of priorities in health

Ebb and flow of priorities in health

POLICY PUZZLER

There are fashions in health policy, as elsewhere, and sometimes they return to favour, writes Tim Tenbensel

We should probably stop using the word ‘solutions’ in the context of health or any other realm of policy

This year’s restructuring of the health system is shaping up as an important episode in the history of health policy in Aotearoa, regardless of what happens in subsequent years.

Any major health policy development needs to be understood in terms of history – but how do we describe and understand that history?

A fairly straightforward approach would be to list the key dates of major government decisions and initiatives.

In 2000, Helen Clark’s Labour Government created district health boards and got rid of the Health Funding Authority. The same Government developed the Primary Health Care Strategy and created PHOs.

John Key’s National-led Government was elected in 2008 and brought in the Better Sooner More Convenient policy. This Government also beefed up the system of national health targets.

When Labour returned to the Government benches, it decided to review the health system and then, in 2021, it decided to abolish DHBs and establish the Māori Health Authority and Health New Zealand.

This history reads a bit like the Book of Genesis (“On the first day, Government created…”). But, as a history, it leaves much unsaid and unexplained.

To make more sense of history, it pays to think of health policy in terms of the problems that governments have attempted to address.

Back in 2000, these problems included the lack of citizen representation in the health system and barriers of access to primary healthcare. By the end of the decade, we had overcrowded emergency departments and poorly integrated health services.

Fast forward to the end of the 2010s and the key concerns were workforce shortages, inadequacy of mental health services, and an overly complex health-system structure. In the early 2020s, leaving COVID-19 aside for the moment, the problem of inequity between Māori and non-Māori has arguably never had a higher profile in government.

So the key historical question to ask is why those problems, and not others, were prioritised at those times? After all, there are so many potential problems in health policy that governments could focus on at any time. But no government has the capacity to focus on all potential problems at all times. There is limited space on the policymaking agenda.

Many big problems in health typically recur – barriers of access to health services, inefficiencies, fragmentation of health service delivery – and the cycle of recurrence does not necessarily coincide with changes of occupants of the Beehive.

An early take on this dynamic was suggested by American economist Anthony Downs, who in the 1970s said policy problems are subject to “issue attention” cycles.

The cycle starts when just a few people perceive something as a problem, but this then develops into a stage of more widespread “alarmed discovery and euphoric enthusiasm”. That is followed by a stage of “realising the cost of significant progress”, which then leads to gradual decline in public interest. After a subsequent period of non-interest, the cycle starts again.

Dr Downs’ issue-attention cycle is useful because it reminds us that big policy problems are not solved, they just fade away in the consciousness of policymakers and the general public. And this cycle also shows that the extent of a problem is only weakly related to the attention it receives at any particular time.

The idea that some policy problems are inherently “wicked” has become highly fashionable in the past decade. Such problems are so beset by uncertainty, ambiguity and debate that they can never be ultimately solved.

Wicked problems are made up of such a tangled knot of political and technical considerations that trying to unravel one part of the knot results in other parts tightening and becoming more intractable.

An interesting effect of this increased interest in the “wickedness” of problems is that everyone sees their pet policy problem as wicked, because pretty much every problem is subject to some degree of uncertainty, ambiguity and contestation. However, wickedness is certainly a matter of degree, and changes over time.

COVID was not particularly a wicked problem in 2020, even though it was a massive issue.

Compared with other issues, there was far less uncertainty, ambiguity and contestation regarding the desirability and feasibility of the elimination strategy

However, COVID certainly became more wicked as time passed. Originally seen as solutions, features such as managed isolation and quarantine, and vaccine mandates became ongoing problems in themselves.

Very often it is difficult to anticipate exactly which other consequences of a policy intervention will become problematic. Just as the virus continues to evolve, so does the problem.

What this all means is that we should probably stop using the word “solutions” in the context of health or any other realm of policy. This does not rule out major advances and improvements. It just reflects that policy never has an end-point – it is always on the move.

For example, the problem of inequities between Māori and non-Māori will not be “solved” once and for all. New dimensions of inequity will be uncovered, and unanticipated consequences of policy responses will undoubtedly crop up. Such problems can be addressed in better or worse ways.

Perhaps the most important effects of the history of defining health policy problems are the organisational legacies they leave behind. We can see this in the continued significance of ACC, Pharmac and Whānau Ora commissioning agencies. We may well see it over future decades with the Māori Health Authority, even though the problem of inequity between Māori and non-Māori is likely to fall from the top of the health policy agenda.

In this column, I have focused on only the history of health policy problems governments have addressed. But we shouldn’t forget there is another history – of health policy problems that, for whatever reason, governments have either not wanted to, or not been able to, address. That’s a whole other can of beans.

Tim Tenbensel is associate professor, health policy, in the School of Population Health at the University of Auckland

FREE and EASY

We're publishing this article as a FREE READ so it is FREE to read and EASY to share more widely. Please support us and the hard work of our journalists by clicking here and subscribing to our publication and website