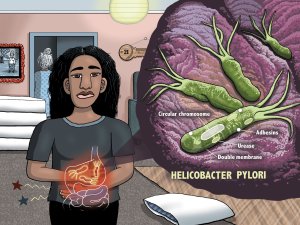

Academic pharmacist Nataly Martini provides key information on Helicobacter pylori pathophysiology, diagnosis and evidence-based treatment strategies to enhance patient outcomes

How the humble limpet helped humans develop, survive and thrive

How the humble limpet helped humans develop, survive and thrive

We are on our summer break and the editorial office is closed until 17 January. In the meantime, please enjoy our Summer Hiatus series, an eclectic mix from our news and clinical archives and articles from The Conversation throughout the year

Louise Firth, University of Plymouth

The humble limpet generally doesn’t attract much attention. Most of us remember them from childhood as tenacious little creatures clinging to rocks, impossible to prise off. But this familiar, cone-shaped animal has played an important part in the development of humans across the globe.

As my recent research underscored, limpets have long been important to humans as food, cultural symbols, offerings in religious and spiritual rituals, and even currency.

From ancient middens to modern cuisine

Unlike mussels and oysters, limpets are now widely seen as a distinctly unfashionable and underused shellfish, despite containing essential vitamins and minerals.

But limpets were harvested for food for hundreds of thousands of years by ancestors of modern humans including Neanderthals, our closest ancient relatives. And around 100,000 years ago, limpets constituted an important part of the diet of Middle Stone Age people.

In fact, it is generally understood that a switch to a seafood diet – fish and shellfish are rich in omega fatty acids which are essential for brain health and vitality – led to the evolution of the large, complex brain of Homo sapiens (modern humans).

Indeed, when modern humans first began to migrate, they often followed coastal routes, so they easily could access a year-round source of nutritious food – including limpets.

Archaeological investigations into prehistoric middens (rubbish heaps) has revealed that not only were limpets eaten all over the world, they were often the dominant shellfish in people’s diets. They were known to have been eaten by ancient civilisations, including the Greeks and Romans, and the early Vikings.

More recently, highly profitable commercial operations in Hawaii, California, Mexico, Chile and the Azores have collapsed due to over-exploitation. But some species of limpet are now highly-prized and considered delicacies in places like Madeira, the Azores and Hawaii. Known as opihi in Hawaii, the limpet is called the “fish of death” because many people lose their lives harvesting them from rocky locations exposed to pounding waves.

Sustaining in times of starvation

Limpets have long been associated with poverty and starvation, and are often referred to as “famine food” or “poor food”. In Scotland, limpets are symbolic of the Highland Clearances (1750-1860) when tenant crofters were evicted from their homes by estate landowners to make way for sheep. Most were driven to hunger and destitution.

This symbolism is epitomised by author Neil Gunn who makes myriad references to eating limpets in his books, which describe the harsh lives of rural communities in the northeast of Scotland in the early part of the 20th century.

In Ireland, too, there are many stories about people surviving off seaweed, limpets and other common shellfish during the many famines that hit the country in the 1800s. Before the 19th century, it was mainly the poor that gathered shellfish from the shore. Such fare was referred to as cnuasach mara (sea pickings).

Many people in Ireland still associate limpets with destitution and starvation, often referring to them as bia bocht – “poor food” or “famine food”. This is perhaps best captured by the old Irish saying: Bia rí isea dúilicíní ach bia tuathaigh isea báirnigh, which translates as “mussels are the food of kings, limpets are the food of peasants”.

Cultural traditions

The importance of limpets as food was even recognised by the famous Greek playwright Aristophanes. His play Assemblywomen on gender equality includes one of the longest words ever (182 Latin characters), which describes a dish that includes limpets by stringing together its ingredients. And here it is:

Limpets were – and are – also popular as bait for catching fish and crustaceans. In Scotland, it could be argued that an entire culture and language has developed around the use of limpets for this purpose, a tradition that is reflected in literature and song.

In the past, limpet shells have been used for a wide variety of uses, including tools, currency, offerings, traditional medicine, jewellery and artworks. The “sailor’s valentine”, which originated in Barbados in the 1830s, is a form of shell craft, a type of souvenir or sentimental gift made from small seashells, with limpets forming a prominent feature.

In Hawaii, limpet shells were placed on shrines, and certain families revered them as their ancestral spirits or “aumakua”. In the east of Scotland, it is thought that limpets were part of the ritual of pagan human sacrifice. For Christians, there is also a strong tradition of eating limpets on Good Friday, particularly around the UK, Ireland and the Azores; the steadfast shellfish is an analogy for the way Christians should cling to God – the way a limpet holds tightly to the rocks.

Its symbolism may be mighty, but the humble limpet has been unjustly underestimated. This marine relative of the familiar terrestrial snail helped humans evolve and provided much needed nutrition and physical and cultural nourishment along the way. It was always so much more than the popular notion of famine food and memories of rock pooling adventures. The limpet deserves some proper recognition at last.![]()

Louise Firth, Associate Professor in Marine Ecology, University of Plymouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.