Academic pharmacist Nataly Martini provides key information on Helicobacter pylori pathophysiology, diagnosis and evidence-based treatment strategies to enhance patient outcomes

Joy at Christmas

Joy at Christmas

Welcome to Pharmacy Today's Summer Hiatus - our seasonal content schedule while Pharmacy Today staff take their summer break.

Today, we have an article taken from our sister publication New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa which featured in the last issue for 2022, written by Ōpōtiki GP and Pinnacle Midlands medical director Jo Scott-Jones

At the end of this course, you should be able to:

- Discuss the benefits of being happy

- Recognise what is important to you and what brings you joy

- Identify where you will focus your time and effort in the next year

- Describe positive approaches to working in general practice

This How to Treat assists with the development of the following domains of competence in the general practice curriculum:

-

Domain 1: Communication

-

Domain 4: Scholarship

-

Domain 5: Context of general practice

A merry Christmas, uncle! God save you!” cried a cheerful voice. It was the voice of Scrooge’s nephew, who came upon him so quickly that this was the first intimation he had of his approach.

“Bah!” said Scrooge. “Humbug!”

He had so heated himself with rapid walking in the fog and frost, this nephew of Scrooge’s, that he was all in a glow; his face was ruddy and handsome; his eyes sparkled, and his breath smoked again.

“Christmas a humbug, uncle!” said Scrooge’s nephew. “You don’t mean that, I am sure.”

“I do,” said Scrooge. “Merry Christmas! What right have you to be merry? What reason have you to be merry? You’re poor enough.”

“Come, then,” returned the nephew gaily. “What right have you to be dismal? What reason have you to be morose? You’re rich enough.”

Scrooge having no better answer ready on the spur of the moment, said “Bah!” again; and followed it up with “Humbug.”

A Christmas Carol, Stave I by Charles Dickens, 1843

What Ebenezer Scrooge, the protagonist in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, learnt was to change his life. This is a moral tale that still resonates with wisdom 179 years later.

Scrooge gained, over the course of Christmas Eve, an understanding of what is really important and a determination to put his time and effort into what truly brings joy.

What is really important to you? Where do you put your time and effort? What brings you joy?

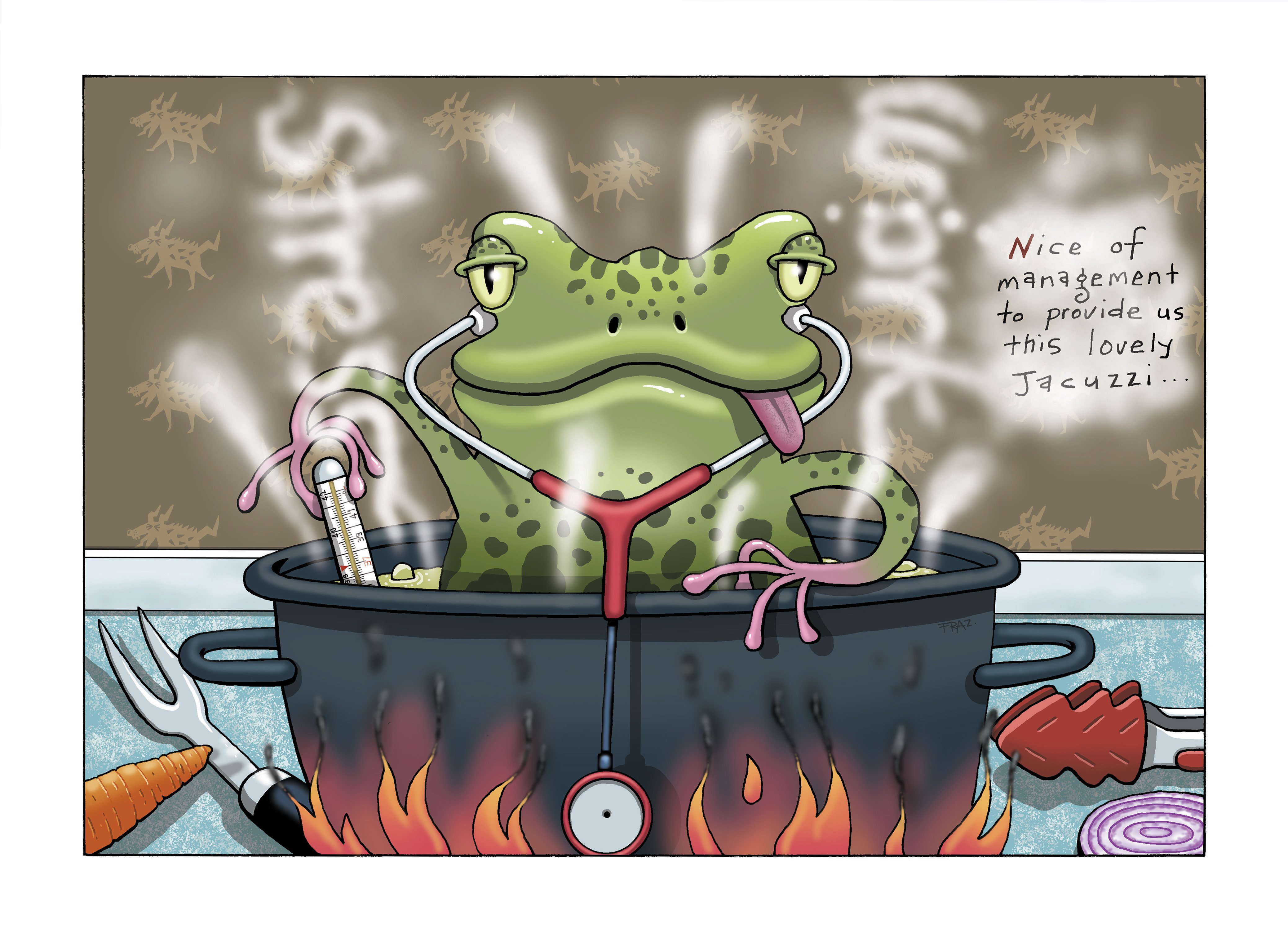

Less poetically, the analogy of “boiling a frog” is an unpleasant image often used to describe how many in our profession have ended up in this soup.

Because the environment around us has slowly become more and more toxic, we haven’t reacted as violently as we might have, had we been suddenly exposed to what we now recognise as a situation incompatible with a happy and comfortable life.

The idea that a frog will not try to escape from a pot that slowly gets hotter is not backed by experimental evidence (watch this video for more than you think you need to know about frogs and hot water: youtu.be/u5Fhek_f6GY).

Like those unpleasantly experimented upon real amphibians, clinicians have either escaped the pan or, in hospitals, flexed their union-strengthened muscles to persuade the curious frog boilers to keep the temperature tolerable.

Your mission this holiday season, should you choose to accept it, is to take time to recognise what is turning up the temperature in your life, think about what is important to you, and decide where you are going to focus your effort in the next year.

Joy (noun)

A feeling of great happiness; a person or thing that causes you to feel great happiness, success or satisfaction. Idioms include “somebody’s pride and joy” and “full of the joys of spring”.

Christmas (noun)

For many families across the globe, Christmas is when time is taken to share more food than is needed, spend more money than is sensible, and resurrect or refresh interpersonal conflict with people with whom they share common patterns of DNA.

In 2022, 176 trials were published on the Cochrane Library with the word “happiness” in the title or abstract (cochranelibrary.com).

These papers suggest that happiness can be increased by: spending money on charity, supporting other people, buying stuff for our pets, having our feet massaged, listening to happy sounding music, eating vegetables, drinking jollab (rose water, saffron and sugar), being part of a group, aromatherapy, interacting with chatbots, exercising outdoors, noting gratitude, meditating, undertaking self-reflection, laughter therapy and placebos.

The impact of negativity on our wellbeing has been articulated for centuries. Hippocrates described melancholia as an imbalance of the four humours, which the Greeks saw had impact on every aspect of the body and mind. Shakespeare referred to “life-harming heaviness” and noted “we are not ourselves when nature, being oppressed, commands the mind to suffer with the body”.

Psychologists today describe the global impact of negative self-talk, and we increasingly recognise conversion disorders and how chronic pain is controlled more by changing understanding than resolving some physical cause.

The impact of negativity on our personal health is clear – it is the antithesis of wellbeing. Its impact on our professional lives and the flow-on effects to our patients may be less obvious to us.

As early as 1964, researchers showed that when an anaesthetist approached a patient with kindness, they spent less time in hospital and needed less pain relief

Unhappiness increases complaints

The health and disability commissioner recently reflected on a 25 per cent increase in the volume of complaints being received, the majority due to delayed treatment associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.1

Commissioner Morag McDowell also wrote that effective resolution relies on “understanding by the provider of people’s concerns and what resolution looks like to that person, a timely empathetic response, acknowledgement of their concerns and any impact it has had on them, commitment to preventive action and, above all, the opportunity to be heard.”1

When we are in hot water and stressed, our stores of empathy are depleted, we find it hard to listen and respond, and we cannot take that empathy and act on it with compassion.

Complaints not only cut deeper when we are less resilient, but they are also more likely to occur. When we lack compassion, patients experience more frustration, overwhelm, and loss of hope and dignity.

Our happiness is good for our patients

When our levels of compassion are high, we are more resilient, we cope better with patients who are suffering or psychologically challenging, and we are less likely to be subject to conflict. And our patients benefit. They have less suffering and less distress, feel more understood, and have more trust in the system. They are more likely to work with clinicians and adhere to a care plan.2

Evidence that healthcare teams with happy staff who have positive communication and connection leads to better outcomes for patients is enticing. This is hard to study, but as early as 1964, researchers showed that when an anaesthetist approached a patient with kindness, they spent less time in hospital and needed less pain relief.3

In their 2014 paper, Kelley and colleagues undertook a meta-analysis of papers describing patient-relevant outcomes (eg, blood pressure and pain scores) influenced by the quality of the relationship with their clinician. While concluding this is hard to study and needs more research, patient outcomes might improve between 2 and 20 per cent when the relationship is good.4

Our happiness is essential to the health system

It would be irresponsible to talk about finding joy in our working life without stating that this is not our responsibility. If you are miserable at work, it is not your fault. You are a victim of the system, which might be doing its best with inadequate resources, but that is not your fault either.

Social sciences describe various models of engagement at work and what influences productivity. Bakker and Demerouti showed that vigour, dedication and absorption at work, leading to better outcomes for everyone, can be negatively impacted by mental, physical and emotional demands, and enhanced by a sense of autonomy, social support, coaching and constructive feedback (Figure 1).5

The health system needs to support its workforce so that we are not overwhelmed. Our employers need to look at what they can do to increase our sense of control at work and how, for example, we can better manage inboxes and complex patient demands.

The US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine indicate six systematic actions that can help prevent burnout in clinicians:6

- facilitating a positive work environment for clinicians

- creating a positive learning environment for trainees

- decreasing the burden of administrative tasks on clinicians

- using technology to create solutions rather than exacerbate problems

- supporting the diagnosis and treatment of burnout by reducing stigma against treatment

- improving the research in this area.

If you are unhappy, it is not your fault, but you can do something about it. It may be a long-term project, but being part of a union if you are an employee, working with colleagues in the same situation if you are an employer, and together helping the system change to become less toxic is empowering and effective.

In the short term, each of us can take some control. Recognising what is in our power and doing what we can to look after ourselves is only sensible.

It is understandable to find yourself in a situation of “learned helplessness” – like Pavlov’s continuously electrocuted dogs, the health service has been barbaric for a long time. You may be lacking energy and just accepting that you are stuck with your lot and must put up with it.

Now is the time to be brave and do something. We will have a miserable time at the work Christmas do, however lavish the party, if we mope in the corner and don’t pick ourselves up and boogie our dignity down on the dance floor.

Tips and tricks to finding joy

Keep a gratitude diary

Journaling is an established intervention to support several mental health conditions, with a reasonable evidence base showing that it can have a small but significant positive impact.7

Taking a few moments at the end of each day to physically write down three things you are grateful for encourages redressing of the natural bias we have of focusing on the negative. You feel like a dork doing it, but a happy dork.

Show and receive affection

Being close to people, connecting with others and interacting in person, if possible, has palpable benefits to your wellbeing.

The rise in reported mental health issues over the COVID-19 pandemic period will have a multifaceted aetiology, but along with the general increase in levels of anxiety, social isolation will have played a part.

The atmosphere at in-person meetings, recent conferences and Christmas social events has been enhanced by the past two years of events being made virtual or cancelled.

Simply being in the same space as other people has benefits, and for those of us lucky enough to have intimate partners, close physical contact has additional impact.

In 2020, the well-respected review team from Alberta who produce the evidence-based, practice-changing Tools for Practice took a tongue-in-cheek look into the evidence around the benefits of kissing. They concluded that a bout of “kissing freely for 30 minutes while listening to soft music may improve surrogate markers of atopy (eg, wheal reactions on allergy test)”.8 This may be why we started doing this stuff as teenagers (or in our late 20s, which is fine – nothing to be ashamed about).

They reviewed another small randomised controlled study that found providing advice to students and college faculty staff to increase the amount of kissing in their lives improved relationship satisfaction and even slightly reduced total cholesterol (by 0.15mmol/L).8

The study involved 52 people (50:50 male/female) aged 19 to 67, and advice given to the intervention group was to “set aside a few minutes each day” to “kiss each other more often”. They were advised to tell their spouse or romantic partner what they had been instructed to do (which was very wise), and the researchers added, “We hope you enjoy this”.8

Advice to increase the amount of kissing led to statistically significant:8

- less relationship conflict compared with control

- improved relationship satisfaction – 5.6 increased to 6.2 (out of 7); control unchanged

- reduced stress – 3.6 reduced to 2.9 (out of 7); control unchanged

- reduced total cholesterol – 4.73mmol/L to 4.58mmol/L; control unchanged.

Mistletoe was not mentioned in either study.

Meditate

I confess I am addicted to my Headspace app and have over one year of daily meditations under my belt now, so I am a believer. The focus of this form of meditation is not on emptying the mind, but on presence and awareness – being “mindful” and fully present and aware at each moment.

Headspace-supported research (so it must be true) has shown that a single 15-minute session of mindfulness meditation increases the ability to focus by 22 per cent. Further, 30 days of practice reduces stress by 32 per cent and increases mental resilience by 11 per cent; and eight weeks of practice decreases anxiety by 19 per cent and reduces depression symptoms by 29 per cent (headspace.com).

On this basis, I should be as relaxed as a jellyfish by now. I’m not, but still, there’s something empirically good about taking a step back every day and reminding yourself that just behind the thundery, stormy thought cloud, there is always clear blue sky and breathing.

Exercise

Laughter has been supplanted by exercise as the best medicine for body and mind.

Lack of exercise is a leading cause of harm, with physical inactivity globally recognised as the fourth highest risk factor for mortality, including increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases, cancer and diabetes.

We recommend our patients engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate activity per week, or 75 minutes of strenuous activity per week, and to do a variety of activities, including muscle strengthening and aerobic activity.9

We all know regular exercise has positive physical and mental health impacts, and improves our sense of self-efficacy and self-worth, but how do we motivate ourselves to actually do it?

A small number of you don’t have this problem. You know who you are – those sleek, slightly sweaty, smug-looking people who we see at medical conferences, still glowing after their morning jog. You have nothing to say here – “just do it” my elbow (editor’s note: you can’t say arse).

For most of us, simply getting out of bed and having a shower can require determination and planning.

The science of motivation tells us that deep in our limbic system, the nucleus accumbens is instrumental in our reaction to potential events and whether we work to enhance a “reward” or avoid a potential “punishment”. We also have drivers that react to “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” stimuli.10

If we want to motivate ourselves to exercise, the same systems apply – we need to boost our sense of reward and avoidance of a punishment, and we need to increase both intrinsic and extrinsic stimuli that drive our behaviour.

How this looks in practice will vary from person to person, but as an example, setting out exercise clothes by the side of my bed makes it easier to get the right gear on for my daily walk or jog. Setting my watch to remind me to do exercise at a certain time each day develops a pattern in my brain that, when broken, makes my day feel less positive.

The extrinsic stimuli of seeing my running shoes, together with feeling and hearing the watch buzz, triggers a response.

The knowledge that a good day usually starts with exercise increases my intrinsic motivation, as does the small shot of dopamine to my nucleus accumbens when I have warmed up a bit, stimulating my reward system.

Anticipating the quizzical look from my wife, when I think about admitting to not having a jog this morning, triggers another flush of dopamine. To avoid the “punishment” of that minor look of disappointment, I head out to shuffle the streets in the cold and wet.

There are lots of ways you can manipulate these motivations to help you set up a regular exercise regimen. Start slow (eg, a couch-to-5km running app or podcast) and share what you are doing with family and friends.

It doesn’t have to be glow-in-the-dark Lycra and gym bunnying; just a regular light jog makes you all shiny.

We all like to do well for our enrolled population. For example, it would really float my boat to get our vaccination rate for Māori tamariki out of the low 50 per cent range and back up to the 95 per cent plus of a few years ago.

We are all familiar with the traditional Plan–Do–Study– Act (PDSA) cycle of change, where we identify the problem we want to solve (eg, poor vaccination uptake) and do a root-cause analysis of why that problem exists (eg, people don’t trust the system the way they used to). Then, we work on addressing the problem (eg, set up a community meeting and community-based vaccination drive), see how we’ve done, learn from that and try something differently.

Appreciative Inquiry is a way of looking at the world in a slightly different way, to achieve the same (and hopefully better) outcomes (Figure 2). It takes a more strength-based and asset-focused approach (looking at what you’ve got to work with), as opposed to the more familiar way of thinking, which tends towards identifying the deficits and trying to solve the weaknesses in the system.

There are PhDs in Appreciative Inquiry who would probably be righteously annoyed at this once-over of their life work. Nonetheless, it is an important approach, and there are masses of online resources and people who will lead you and your team in Appreciative Inquiry workshops – hunt them down. A good starting point can be found at What Works (whatworks.org.nz/appreciative-inquiry).

Next time you are looking at your Māori health plan, consider consciously taking this approach and see how it feels. Ask yourself:

- Who are the patients who are accessing the service?

- What is working well for them?

- How can we do more of that?

- When we are working at our best, how does that impact our services?

- How can we work well more often?

- What would excellent look like?

- What can we practically do to get us there?

- What are the three actions we could take that will have the maximum benefit?

- What worked well in that approach?

- How can we maximise and build more of what we did well?

I can guarantee that taking this positive spin on exploring solutions will be energising for your team and have more impact for your people.

Build joy at work

Over the course of several years, I have gathered stories of what brings joy to GPs from around the world, and what they do to enhance that joy.

Take a moment to write down a sentence about what is satisfying about your working life, what makes a good day and what brings you joy at work.Take another moment to write down what you and your team do that allows that thing to happen more often.

At your next practice meeting, ask everyone to do the same. Pin the notes on your notice board and share some ideas about how you can collectively do more to build joy into your day.

For more ideas about what brings others joy in practice, and a monthly update on clinically important stuff, check out The New Zealand General Practice Podcast (tinyurl.com/NZGPpodcast; editor’s note: do you have no shame?).

The UK National Health Service’s 15s30m (15s30m.co.uk) is a social movement that shows how to create a culture of kindness and continuous improvement. Doing something that takes you 15 seconds, but provides 30 minutes of benefit to colleagues in your team, is easier than you’d think.

Recent 15s30m ideas include the following:

- Classify “abnormal liver function tests” and make a note of the monitoring required, so every time your colleagues are working on your inbox, they know those mildly disordered LFTs are known about and that there is a plan – 15 seconds to do, collectively saves multiple minutes of searching through the past history to understand.

- Keep all the commonly used equipment (foetal Doppler, dermatoscope, point-of-care ultrasound) in a central store and return it when it’s used – 15 seconds to do, saves minutes of searching the surgery for the shared resources.

- Have a common layout for equipment in each clinical room – 15 seconds to do, saves locums and other people using a shared room collective minutes of searching for a throat swab or glucometer.

- Have a process for replacement of stock as it starts to run out – 15 seconds to do, saves time hunting around or borrowing gear from neighbouring clinics.

Once your team starts on a 15s30m plan, you will find multiple opportunities for small changes.

First, you save yourself

Take a moment this holiday season to refresh your knowledge of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. Then, work out what is truly important to you, and where you will spend your time and effort over the next year.

Merry Christmas!

“A merry Christmas, Bob!” said Scrooge, with an earnestness that could not be mistaken, as he clapped him on the back. “A merrier Christmas, Bob, my good fellow, than I have given you, for many a year! I’ll raise your salary, and endeavour to assist your struggling family, and we will discuss your affairs this very afternoon, over a Christmas bowl of smoking bishop, Bob! Make up the fires, and buy another coal-scuttle before you dot another i, Bob Cratchit!”

A Christmas Carol, Stave V by Charles Dickens, 1843

Jo “Bah Humbug” Scott-Jones is medical director for Pinnacle Midlands Health Network, has a general practice in Ōpōtiki and works as a specialist GP across the Midlands region

You can use the Capture button below to record your time spent reading and your answers to the following learning reflection questions:

- Why did you choose this activity (how does it relate to your professional development plan learning goals)?

- What did you learn?

- How will you implement the new learning into your daily practice?

- Does this learning lead to any further activities that you could undertake (audit activities, peer discussions, etc)?

We're publishing this article as a FREE READ so it is FREE to read and EASY to share more widely. Please support us and the hard work of our journalists by clicking here and subscribing to our publication and website

1. Health and Disability Commissioner. Rise in complaints unprecedented. 2022.

2. Malenfant S, Jaggi P, Hayden KA, Sinclair S. Compassion in healthcare: an updated scoping review of the literature. BMC Palliat Care 2022;21(1):80.

3. Egbert LD, Battit GE, Welch CE, Bartlett MK. Reduction of postoperative pain by encouragement and instruction of patients. A study of doctor-patient rapport. N Engl J Med 1964;270:825–27.

4. Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, et al. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2014;9(4):e94207.

5. Bakker AB, Demerouti E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev Int 2008;13(3):209–23.

6. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-being. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019.

7. Sohal M, Singh P, Dhillon BS, Gill HS. Efficacy of journaling in the management of mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Med Community Health 2022;10(1):e001154.

8. Lindblad AJ, Korownyk C, Falk J, et al. What’s under the Mistletoe? Some fun holiday evidence from PEER. Tools for Practice #279, 14 December 2020. gomainpro.ca/tools-for-practice

9. Hechanova RL, Wegler JL, Forest CP. Exercise: A vitally important prescription. JAAPA 2017;30(4):17–22.

10. Kraus J. 4 Motivators for Productivity and the Science Behind Them. Zapier, 9 August 2018.