Academic pharmacist Nataly Martini discusses the medical management of asthma in adults and adolescents, which has evolved to prioritise early anti-inflammatory treatment. She also explains how to improve patient outcomes by proactively identifying poor asthma control and supporting equitable access to education and treatment

Deconstructing coughs, colds and effective management strategies

Deconstructing coughs, colds and effective management strategies

Clinical writer Noni Richards discusses the effective management of upper respiratory tract infections, including symptom assessment, patient education, appropriate product recommendations and preventive strategies

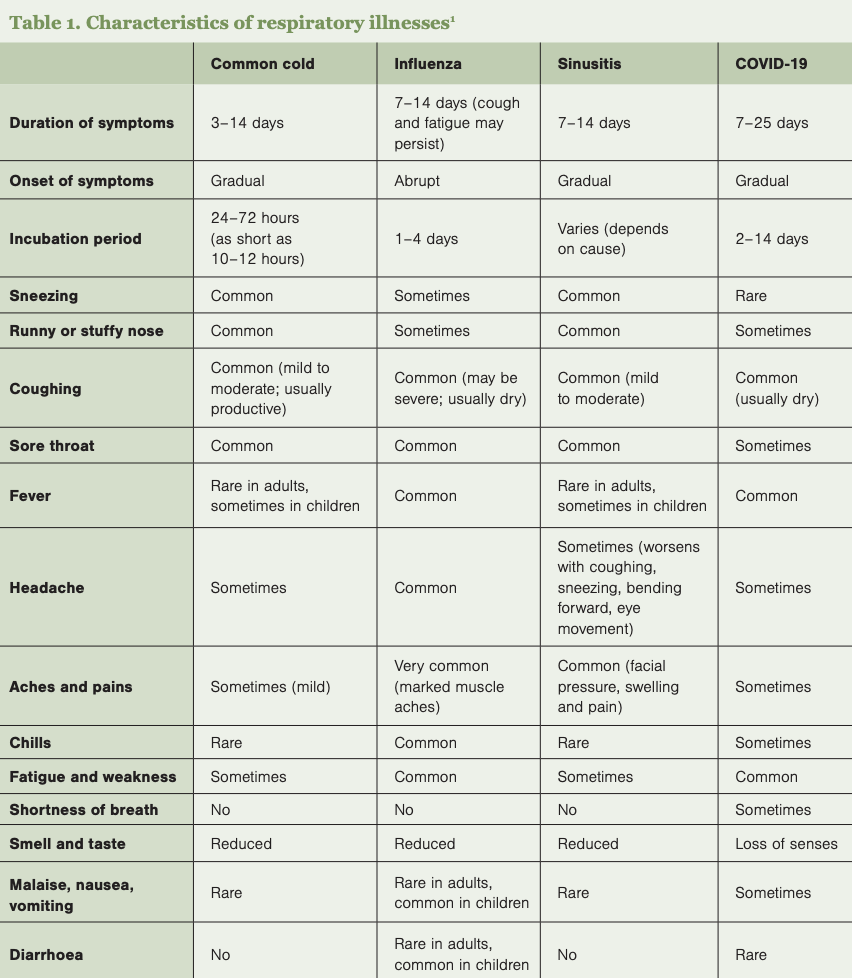

Upper respiratory tract infections, including the common cold, influenza and sinusitis, are prevalent conditions that pharmacists frequently encounter. It is important to assess symptoms to distinguish between different URTIs (Table 1) and determine whether referral is needed. A thorough patient history would include asking about the onset, duration and severity of symptoms, as well as any underlying health conditions.

Key symptoms to evaluate:

- Cough – characterise it as productive (with phlegm) or non-productive (dry).

- Nasal congestion – assess severity and impact on daily activities.

- Sore throat – determine intensity and associated symptoms.

- Fever – check/enquire about temperature and duration.

Red flags warranting referral:1

- High fever (eg, ≥39ºC in adults or ≥38ºC in children) unresponsive to antipyretics.

- Fever lasting five or more days or returning after a fever-free period in adults.

- Rising fever or fever lasting more than two days in children.

- Worsening or persistent symptoms in children.

- Excessive irritability, poor feeding or loss of appetite in children.

- Bulging fontanelle on a baby or child’s head.

- Meningitis symptoms – severe headache, stiff neck, high fever, light sensitivity.

- Confusion, vomiting, severe diarrhoea or dehydration.

- Sore throat lasting more than two weeks.

- Sore throat, fever, swollen glands and marked tonsillar exudate.

- Sore throat with difficulty swallowing.

- Sore throat with mouth ulceration, blistering or skin rashes (may be agranulocytosis, which can be medicine induced).

- Persistent cough – lasts over three weeks or recurs regularly.

- Unusual sputum with cough – discoloured, purulent or contains blood.

- Chest pain (may be cardiovascular).

- Breathing issues – shortness of breath, wheezing, stridor or pain on inspiration.

- Cough worsens an existing condition (eg, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

- Persistent night-time cough in children (possible asthma).

- Severe cough in older people.

- New or changed cough in people aged 45 and over who smoke, or in those who are immunocompromised.

About half of sore throat cases are viral (eg, rhinovirus, influenza, Epstein–Barr), while the other half are caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus or GAS). GAS infections tend to be more severe, but clinical assessment alone cannot distinguish between viral and bacterial causes. Antibiotics offer no benefit for viral sore throats and only reduce GAS symptoms by about two days. Most sore throat cases do not require testing or antibiotics.2

However, in high-risk individuals, particularly Māori and Pacific peoples aged three to 35, GAS infections can lead to rheumatic fever. To reduce this risk, throat swabs should be tested for GAS in patients with a personal, family or household history of rheumatic fever or those meeting at least two of the following criteria: Māori or Pacific ethnicity; aged three to 35; living in crowded or lower socioeconomic conditions. For these patients, a throat swab should be taken when starting empiric antibiotics (a 10-day course of amoxicillin). If GAS is not detected, antibiotics can be stopped.3

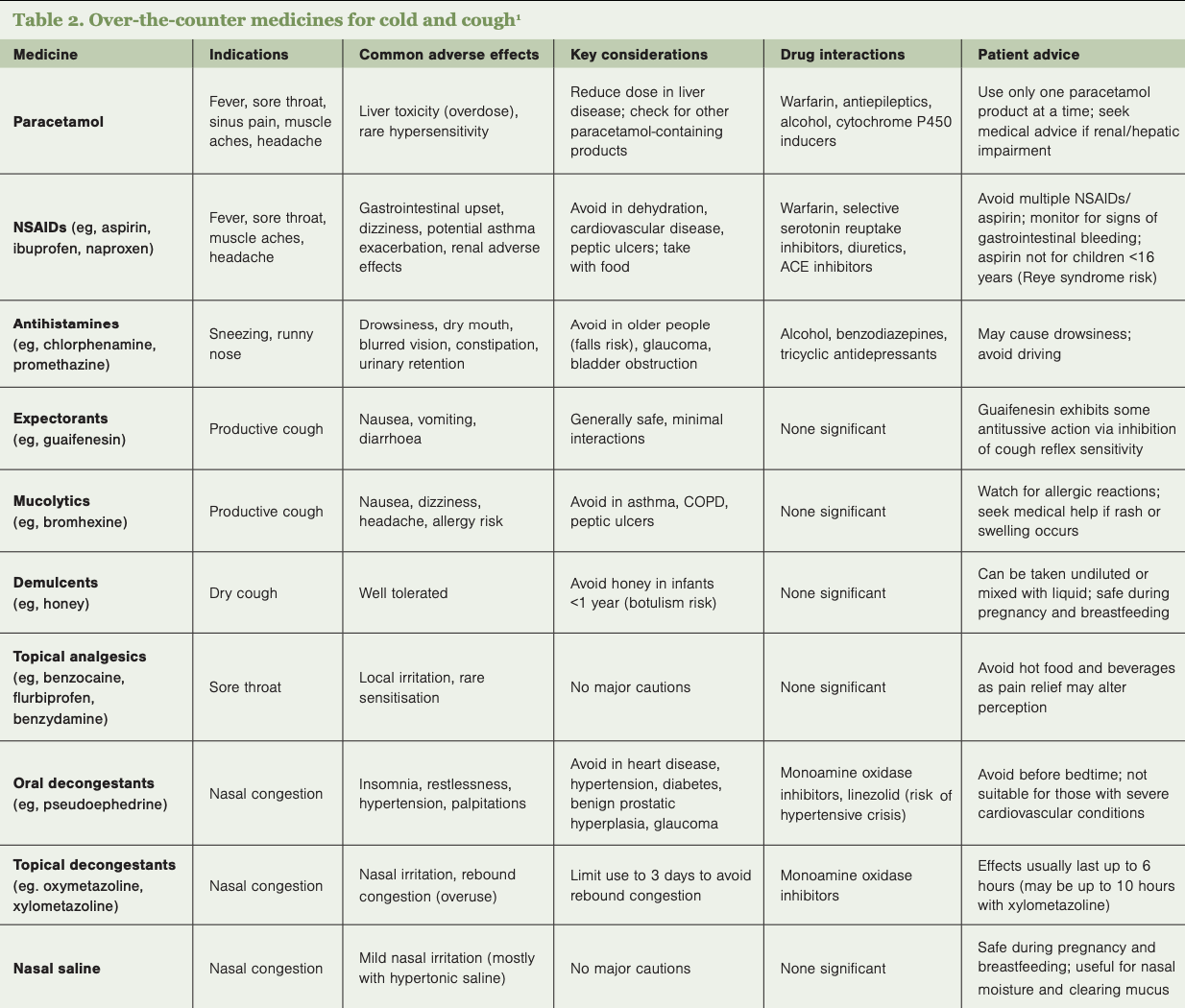

As most colds and coughs are self-limiting, a variety of over-the-counter products are used to help relieve symptoms and improve comfort until recovery (Table 2). Patients should be guided to select appropriate treatments and cautioned against the concurrent use of multiple products containing similar active ingredients to prevent overdose.

Analgesics/antipyretics – paracetamol and NSAIDs (eg, ibuprofen) are effective at managing fever, aches, headaches and sore throat. Due to its safer profile, paracetamol is the preferred first-line option for patients with multiple conditions or taking other medicines. Care should be taken to avoid exceeding the recommended dosage, especially when used with other combination cold products that contain paracetamol. Exceeding 4g of paracetamol daily can cause liver toxicity. NSAIDs carry higher risks of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and renal side effects, especially with dehydration.4

Decongestant nasal sprays – medicines such as xylometazoline provide quick relief of nasal congestion by constricting nasal blood vessels. However, use should be limited to three consecutive days to avoid rebound congestion. More prolonged use can lead to rhinitis medicamentosa with nasal mucosa changes.1,4

Oral decongestants – pseudoephedrine is effective but may cause systemic adverse effects, such as increased heart rate and insomnia, and is contraindicated for people with severe coronary artery disease.4

Expectorants and mucolytics – these medicines aim to loosen mucus in productive coughs. Guaifenesin (expectorant) may help to expel mucus from the lungs, and bromhexine (mucolytic) may help break down thick, sticky phlegm and make it easier to cough up. However, evidence supporting either medicine’s effectiveness is limited.5

Cough suppressants (antitussives) – dextromethorphan and pholcodine were commonly used for dry, non-productive coughs. However, pholcodine-containing medicines were withdrawn in New Zealand from January 2024 due to safety concerns.6 Dextromethorphan products are no longer supplied in New Zealand, with most approvals lapsing after its reclassification in 2019 as a pharmacist-only or prescription medicine.7

Complementary treatments – aside from antitussives, which have minimal effect, no medicines effectively treat dry cough. However, complementary treatments such as honey, glycerol syrups, vapour rubs, ivy leaf extract and zinc may help reduce cough frequency or severity.2,7,8

Lozenges and throat sprays – products containing local anaesthetics, antiseptics or anti-inflammatory agents can provide temporary relief of sore throat and relieve a dry, irritating cough.

Over-the-counter cough and cold medicines are generally not recommended for children under six years

Paracetamol and ibuprofen can be used in children for fever and pain relief if required. OTC cough and cold medicines are generally not recommended for children under six years due to limited efficacy and potential for serious adverse effects.1,9 Non-pharmacological approaches are preferred:

- Honey – for children over one year, honey can be an effective remedy for cough relief.2 It should not be given to infants under one year due to the risk of botulism.8

- Saline nasal drops – these can help alleviate nasal congestion in infants and young children and are considered safe.

- Vicks VapoRub – has been shown to reduce nasal congestion and cough frequency and severity when applied before bedtime, improving child and parental sleep.2

Educating patients on preventive measures can help reduce the incidence and severity of colds and coughs. For example:

- Regular handwashing with soap and water is one of the most effective ways to prevent the spread of infections.

- Covering the mouth and nose with a tissue or elbow when coughing or sneezing minimises transmission.

- Annual influenza vaccinations are recommended, particularly for high-risk populations.

When recommending OTC products for cold and cough symptoms, it is important to set realistic expectations. These products can help ease discomfort, but they do not shorten the duration of a cold, which typically resolves on its own within seven to 10 days. Encourage patients to prioritise rest and self-care as part of their recovery.

Noni Richards is a registered pharmacist and a senior researcher at Matui

1. International Pharmaceutical Federation. Cold, flu and sinusitis: Managing symptoms and supporting self-care: A handbook for pharmacists. The Hague: International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2021.

2. Antibiotic Conservation Aotearoa.

3. Heart Foundation. New Zealand Guidelines for Rheumatic Fever. Group A Streptococcal Sore Throat Management Guideline: 2019 Update. Auckland, NZ: Heart Foundation; 2019.

4. New Zealand Formulary. NZF v153; 1 March 2025.

5. Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014(11):CD001831.

6. Medsafe. Alert Communication: Consent to distribute pholcodine-containing medicines will be revoked on 12 January 2024. Medsafe Safety Communication, 25 September 2023.

7. BPACnz. Cough medicines: do they make a difference? 31 May 2024.

8. Pope C (Tech Ed). Healthcare Handbook 2024–2025. Auckland, NZ: The Health Media Ltd; 2024.

9. Medsafe. Use of Cough and Cold Medicines in Children – Updated advice. Medsafe Safety Communication, 28 May 2013.