Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a fairly new and exciting area of research in psychiatry. In this article, Sidhesh Phaldessai examines our increasing understanding of the symptom presentation and management of this neurodevelopmental disorder in adults

Think pertussis! Maternal and on-time infant vaccinations are essential

Think pertussis! Maternal and on-time infant vaccinations are essential

Aotearoa is likely to be on the verge of a pertussis outbreak, with recently reported cases just the tip of the iceberg – are you and your patients ready? Mary Nowlan and Nikki Turner from the Immunisation Advisory Centre discuss what you need to know

Pertussis (whooping cough) is one of the most transmissible vaccine-preventable diseases, and more infectious than COVID-19. Pertussis epidemics generally occur every three to five years in Aotearoa – our last official epidemic ran from October 2017 to May 2019.

Control measures put in place for COVID-19 reduced other respiratory infections, but now pertussis has already begun to emerge in young infants – a tragic, early signal of wider community outbreaks. Paediatricians are dismayed and frustrated that this could happen when a highly effective vaccine is available in pregnancy to help to prevent this horrific disease in infants.

It is important to be alert to individuals of any age with prolonged coughing – don’t risk assuming it is a post-COVID cough when it could be pertussis.

The initial stage of pertussis, lasting for one to two weeks, is the most infectious, with insidious onset of a runny nose and an irritating cough that can progress to severe coughing fits. During this stage, the only clue to diagnosis may be contact with a known case.

The disease progresses to include paroxysmal coughing episodes, characterised by a series of short expiratory bursts, followed by an inspiratory gasp or typical whoop, and/or vomiting. This stage can last from one to six weeks, and even up to 10 weeks.

The communicable period starts from the initial catarrhal stage to three weeks after the onset of the paroxysmal cough, if not treated with antimicrobials.

Clinical presentation of pertussis varies with age, immunisation status and previous infection. Infants are more likely to present with gagging, gasping, cyanosis, apnoea, or non-specific signs such as poor feeding or seizures. They are less likely to have the inspiratory whoop. Adults and children partially protected by vaccination can present with illness ranging from a mild cough to classic pertussis.

Virulence factors secreted by Bordetella pertussis, notably pertussis toxin (PT), damage the ciliated epithelial cells in the airways and disable immune cell migration and function. As well as respiratory effects, PT causes systemic immune and metabolic disturbances and brain toxicity. In small bodies, these effects are amplified. Pertussis in infants can lead to intractable pulmonary hypertension associated with extreme lymphocytosis and bronchopneumonia.

In these severe cases, there is little that can be done except for critical care support for the infant’s damaged lungs via extracorporeal membrane oxygenation bypass. Even infants who are not so severely ill have periods of apnoea, hypoglycaemia and other metabolic changes that can result in long-term brain or respiratory damage.

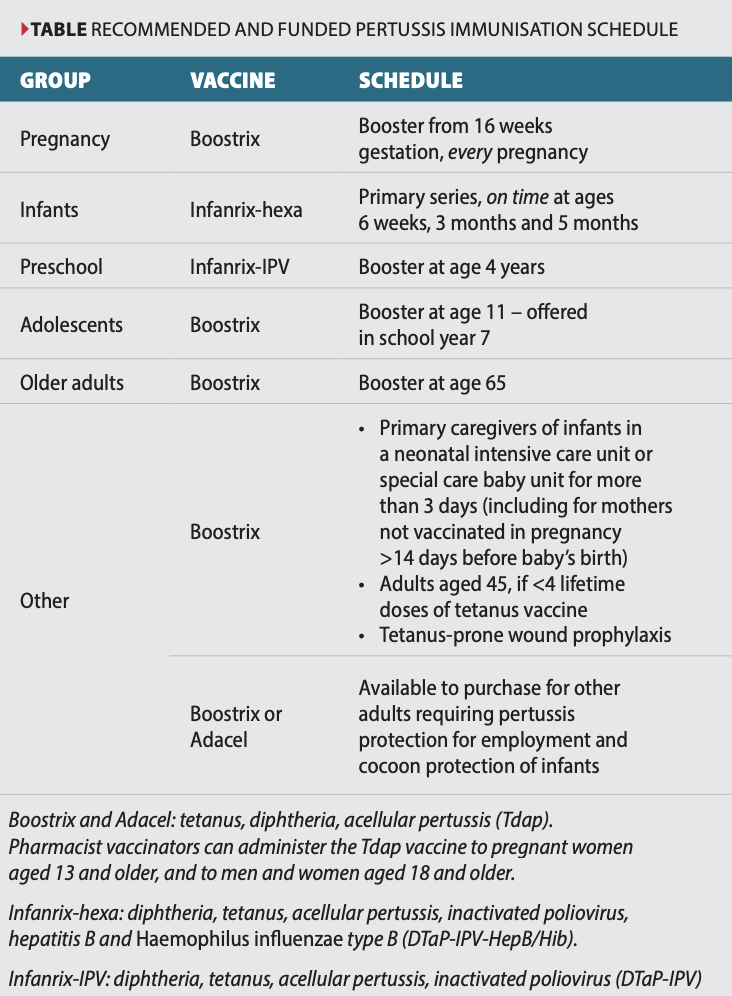

Antibodies block attachment of, and neutralise, PT and other virulence factors to prevent bacterial invasion and symptomatic illness. Protection is not long lasting, and for this reason, vaccine booster doses are recommended for all individuals working with young children, during each pregnancy, at age 65 and for other high-risk groups (see table).

A range of studies have shown that in over 70 per cent of identified pertussis cases, new babies caught pertussis from their parents or other close family members. Immunisation of both parents can provide some protection and may be considered postpartum if antenatal vaccination does not occur. However, evidence is weak for cocooning strategies with pertussis-containing vaccine, as infants can be exposed to pertussis outside of the family environment.

Ensure all children are up to date with their vaccinations, including booster doses at ages four and 11 years (see table). It is advisable to keep family members and contacts with coughs away from infants, when possible.

Maternal pertussis antibodies, transferred across the placenta, offer infants short-term but effective protection against severe pertussis by neutralising PT before it can affect the immune system. Antibodies in breast milk cannot prevent the systemic effects of circulating PT.

Maternal vaccination is more than 90 per cent effective in preventing pertussis in infants when received at least seven days before birth. Studies have shown higher cord-blood antibody concentrations protect the newborn for longer. Vaccination is ideally given at 16–24 weeks gestation. This allows time for antibodies to accumulate but not wane before birth, and it provides vital protection for preterm infants.

Boostrix administered during pregnancy protects both the mother from symptomatic pertussis and provides passive protection for her new baby for approximately six months, until fully immunised themselves.

No safety concerns have been identified when Boostrix is given during pregnancy, with similar rates of pregnancy complications and birth outcomes seen in vaccinated and unvaccinated women.

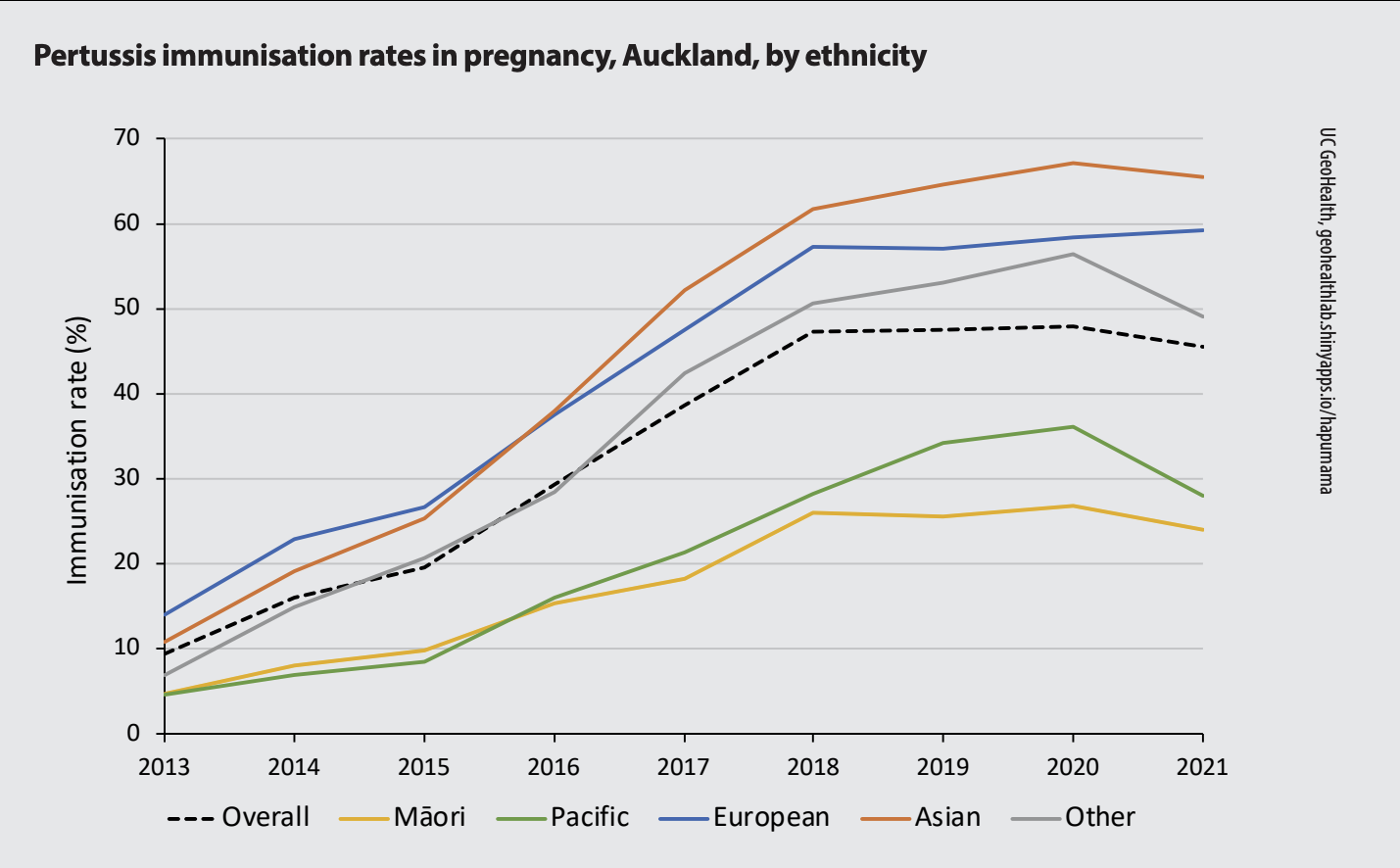

Unfortunately, the uptake of pertussis and influenza vaccines in pregnancy is too low in Aotearoa. Accurate data are lacking, but based on National Immunisation Register and claims data (GP and pharmacy) from 2013–2018, uptake began to increase, from 10 to 44 per cent for pertussis vaccine, and from 11 to 31 per cent for influenza vaccine.

Nationally in 2021, overall maternal immunisation coverage for pertussis vaccination ranged by district from 12.5 to 69 per cent (see figure for Auckland coverage by ethnicity). For comparison, in England, maternal coverage was 60–70 per cent in 2022.

Younger women and those living in high deprivation are less likely to be vaccinated in pregnancy.

Effective communication and positive recommendations from trusted healthcare professionals improve maternal vaccine uptake. A range of coordinated, knowledgeable health contacts is needed during pregnancy to aid with informed decision-making.

Barriers for accessing vaccination during pregnancy include a lack of awareness about the vaccines, lack of transport to vaccine providers or maternity care, late presentation to midwifery, and other commitments and challenges affecting prioritisation of immunisation.

Antenatal vaccination should be counted as an infant’s first dose of pertussis vaccine. Starting at age six weeks, on-time vaccination is especially important for infants whose mother was not vaccinated in pregnancy, and for protection against other diseases. Timely administration of the subsequent doses at ages three and five months ensures that all infants are fully protected by six months.

Parents who accept vaccines in pregnancy generally vaccinate their infants on time and develop a positive approach to immunisations for the whole whānau.

Be alert for pertussis – it is a notifiable disease.

Antibiotics can reduce infectivity and modify the clinical course of the illness if administered during the catarrhal stage or the early paroxysmal stage (usually the first two weeks). Pertussis immunisation after exposure will not prevent nor reduce severity of disease. High-priority contacts are identified for public health follow-up and chemoprophylaxis, if appropriate.

Further information about pertussis immunisation and vaccinations in pregnancy can be found on the Immunisation Advisory Centre website (immune.org.nz). Also refer to chapter 15 of the Immunisation Handbook 2020 (tinyurl.com/ImmHandbook20) and the Communicable Disease Control Manual (tinyurl.com/CDCM-Pertussis).

Mary Nowlan is a medical writer and senior advisor at the Immunisation Advisory Centre. Nikki Turner is a GP and medical director at IMAC

- Amirthalingam G, Campbell H, Ribeiro S, et al. Sustained effectiveness of the maternal pertussis immunization program in England 3 years following introduction. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63(Suppl. 4):S236–43.

- Bechini A, Tiscione E, Boccalini S, et al. Acellular pertussis vaccine use in risk groups (adolescents, pregnant women, newborns and health care workers): a review of evidence and recommendations. Vaccine 2012;30(35):5179–90.

- Howe AS, Pointon L, Gauld N, et al. Pertussis and influenza immunisation coverage of pregnant women in New Zealand. Vaccine 2020;38(43):6766–76.

- Melvin J, Scheller E, Miller J, et al. Bordetella pertussis pathogenesis: current and future challenges. Nat Rev Microbiol 2014;12:274–88.

- Petousis-Harris H, Jiang Y, Yu L, et al. A retrospective cohort study of safety outcomes in New Zealand infants exposed to Tdap vaccine in utero. Vaccines (Basel) 2019;7(4):147.

- Radke S, Petousis-Harris H, Watson D, et al. Age-specific effectiveness following each dose of acellular pertussis vaccine among infants and children in New Zealand. Vaccine 2017;35(1):177–83.

- Sukumaran L, McCarthy NL, Kharbanda EO, et al. Association of Tdap vaccination with acute events and adverse birth outcomes among pregnancy women with prior tetanus-containing immunizations. JAMA 2015;314(15):1581–87.

- Wendelboe AM, Njamkepo E, Bourillon A, et al. Transmission of Bordetella pertussis to young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007;26(4):293–99.

- Wiley KE, Zuo Y, Macartney KK, McIntyre PB. Sources of pertussis infection in young infants: a review of key evidence informing targeting of the cocoon strategy. Vaccine 2013;31(4):618–25.